Heritage Foundation Labor Event: Unelected Representatives

By Olivia Grady

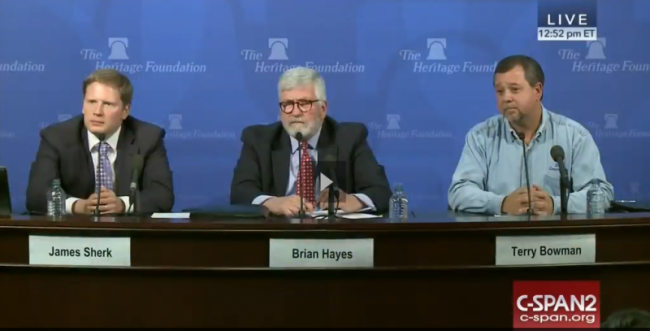

James Sherk, a labor economist at the Heritage Foundation, hosted a panel at Heritage on September 1, 2016, called “Unelected Representatives: 94 percent of Union Members Never Voted for a Union.” The event highlighted new research published by Sherk and his team regarding the undemocratic nature of union representation. Sherk was joined by other panelists: Brian Hayes, a former member of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and Terry Bowman, a former United Auto Workers (UAW) union member at Ford.

Mr. Sherk began the discussion by explaining some circumstances where unions and their members disagree. For example, unions negotiate wages, benefits, work hours, etc., but individual workers can’t negotiate for themselves even if the union bargain doesn’t help them. In addition, they sometimes can’t accept pay increases if it’s based on performance pay, rather than seniority (unions don’t like performance pay since it removes their role).

This however wasn’t what the National Labor Relations Act was designed to do. Unions were intended to represent their workers.

In his study, Shirk also discovered that only 6 percent of unionized workers actually voted for the union.

He gave four main reasons why workers never voted for their union: There is turnover so the original supporters of the union are usually no longer working at the business, and there are no re-elections; Unions just have to secure support from a majority of the workers who voted, not the entire group of workers, and many don’t vote; It is very difficult for workers to get rid of the union; and Unions don’t have to hold elections if the employer doesn’t have a secret ballot election.

As a result, there is a high level of dissatisfaction among members – 70 percent disapprove of their union. One recent example of the dislike of unions by workers occurred when Volkswagen autoworkers in Tennessee voted heavily against the union.

In addition, two thirds of workers think union representatives are representing themselves, rather than the workers.

In concluding, Sherk mentioned a case that proves this belief: UNITE HERE claims to represent hotel workers in California. Union representatives there recently lobbied for a higher minimum wage for only nonunion workers. Thus, they were able to unionize many hotels and collect more dues because hotel employers didn’t want to pay the higher minimum wage. However, since the higher minimum wage didn’t apply to union workers, the union did not actually increase wages for their workers.

Brian Hayes next spoke about the lack of accountability for unions since there are no re-elections. He mentioned how difficult it is to get rid of the union; there are only two ways. One way is decertification where the employees petition the NLRB for a new vote.

However, the NLRB has many rules that prevent workers from decertifying. For example, the contract bar rule doesn’t allow a decertification within three years of a contract except for a very short window period. Another example is the blocking charge rule, which can substantially delay a decertification effort if the union charges an unfair labor policy during a decertification. In addition, the employees have very little help, and employers can’t help them.

Finally, the current NLRB has made this process even more difficult. In 2011, it decided that there would be an presumption that the workers still want a union even when the employer sells the business. That is rather than give workers a choice of whether to continue to be represented by the union after the sale of the business, there has to be concrete evidence that they don’t want a union – a high burden to obtain.

Another example is that if an employer voluntarily recognizes a union, there is a presumption of union support for at least six months. The result of these new rules has been a large decrease in the number of decertification petitions filed – roughly half since 2006.

The second process for getting rid of the union is the unilateral withdrawal of representation by the employer if the employer has evidence that the workers don’t want to be represented by the union. However, recently, the NLRB ruled that there has to be an election before the employer withdraws representation.

The final speaker was Terry Bowman, a Michigan resident who started working at Ford in 1996. It was his first time in a union (UAW), and at that time, Michigan was not a right-to-work state (he later gave up his union membership when Michigan became a right-to-work state in 2012).

His talk included some history of the UAW. The UAW interestingly was formed at Ford in 1941 for autoworkers, although it has since started claiming to represent public sector workers and even graduate students at private universities. He then explained that none of the current workers voted to be represented by the union, and he supports regular re-certification elections. He believes they would help workers because union representatives aren’t representing their workers these days.

He gave some examples: Representatives aren’t always at the factory where their workers are because sometimes they are playing golf; Representatives take trips to nice destinations on workers’ money; In 2014, the UAW raised dues by 25% at one time; Cronyism is present; Favoritism, in terms of i.e. promotion opportunities, exists if a worker supports the union by i.e. going to union events; and There is an insulting push to vote for union demands.

He also talked about the fear and intimidation tactics that unions use to prevent decertification efforts.

Bowman ended his conversation with promoting the Employee Rights Act, which gives more rights to union workers, and he stressed that competition and re-certification elections will make unions better.

Interestingly, this lecture brought to my mind some of the issues experienced in the decertification by Minnesota homecare workers, which the Center for Worker Freedom is actively supporting. For example, only about 5,000 homecare workers out of about 27,000 voted in the election, and only about 3,500 voted for the union. Despite this, all 27,000 became members of the collective bargaining agreement. In addition, the challenges the panel mentioned with decertification have proven true.

To learn more about this event and to watch the video, please click here, or to read about James Sherk’s research, click here.